Why we could be alone after all

We don’t know how many stars there are in our own galaxy, let alone any of the other estimated 100 to 200 billion galaxies that make up the observable universe, but a ballpark figure often quoted is around the 100 billion mark. That’s a lot of stars, I guess.

| The hasty generalisation fallacy

Assuming that every star has at least one planet in orbit around it, a back-of-the-envelope calculation tells me that there should be between 10,000,000,000,000,000,000 and 20,000,000,000,000,000,000, or 10 to 20 quintillion planets. That’s so many planets that even your eyes could not quite comprehend the number of zeros in each number, and you skipped on past it until you came back to something you could understand. Imagine trying to comprehend that number of actual planets. That’s a lot of planets. Possibly.

Let’s average that out and say fifteen quintillion planets. Now, let’s make an assumption based on nothing whatsoever, and say that perhaps one in every thousand planets, in the habitable zone around its star, meaning that if it contained water, it would be in liquid form. That leaves you with fifteen quadrillion, or 15,000,000,000,000,000 planets that could possibly harbour life. That’s a lot of life. Potentially.

It’s these types of calculations that are regularly offered up as irrefutable proof that we could not possibly be alone in the universe. With more planets capable of hosting life than the human brain can even comprehend, it would be a near impossibility for ours to be the only one to have succeeded. To assume any different would demonstrate such a degree of arrogance that it’s difficult for many to even tolerate.

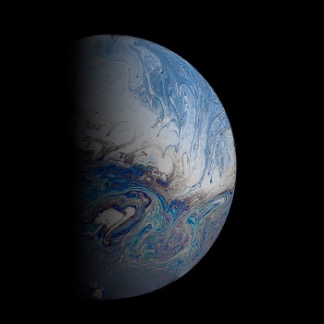

However, this type of argument is, in my view, a fallacy which both assumes and ignores too much to make it a valid argument. It doesn’t take into account the countless events and processes that had to occur either on the Earth or to the Earth in order for life to have not only started in the first place, but continued to exist and thrive into the beautiful, multi-celled, and in one instance at least, intelligent and self-aware forms of life that exist today on this pale blue dot, trapped in a sunbeam, as the late Carl Sagan so poetically put it.

The factors which have all played their own unique role in the story of life on Earth are so numerous that a small article such as this could not possibly suffice in detailing them all. I would probably have to write a book on the subject, as others have done, and even then it wouldn’t cover all of them sufficiently. But let’s use the time and space that we do have here and now to cover some of the most clear and obvious ones.

| Abiogenesis

Let’s start with what’s known as abiogenesis. This is the theory that, as far as scientists can tell, life has only begun on Earth once. We still have no clear idea how or where life began, but the code in our cells appears to trace back to a single event about 3.5 billion years ago when, for the first and only time, something that wasn’t alive somehow became alive. It’s a fact that is not often discussed when debates around life on other planets take place, which I always find fascinating. Perhaps it’s because, when we look around at the abundance of living things on our spinning rock, it’s easy to forget that it is, as far as we know, all the result of an incredibly long chain reaction. A chain, nonetheless, that once began with only a single link on one side.

Despite our almost godlike abilities to manipulate cells and the DNA they are composed of, we still have a long way to go before we have the ability to create life from nothing in a test tube, despite numerous and ongoing attempts. This leaves us with yet another uncomfortable assumption: if life in the universe is as inevitable as many like to assume, why then has life not arisen multiple times on Earth, and why does it not continue to arise today? Our tree of life may have grown to be unfathomably large, but why does it appear as though it’s the only tree in the forest?

It’s possible that the reason why life does not continue to spontaneously come into existence today is that the specific conditions needed for life to begin are no longer present, and that life could only have started during the period of Earth’s history when the conditions were just right. But if this were true, it would only narrow down even further the odds of life getting going at all. If life can only begin when very narrow and specific conditions are met, how many other planets have ever met the same criteria? When we look at just our own solar system, comprised of eight very different and unique planets, only one, Mars, appears to have perhaps had the right conditions for life at some point in its history. But even then, we have yet to find any solid proof that it did.

| The wasteful nature of nature

When we look out towards the vastness of space, at the incomprehensible number of stars and galaxies, and draw the conclusion that we cannot possibly be the only planet with life, not to mention intelligent life, what we are really questioning is: surely nature could not be so wasteful? If we really were the only life in the universe, that’s a hell of a lot of empty space simply going to waste. But to say this is to give the universe purpose and meaning. It is placing a value that is, as far as we can tell, uniquely human, on something that is not human and therefore doesn’t have human values. Nature is littered with examples of waste. For example, and I won’t go into too much detail here, but a little Googling and some more back-of-the-napkin calculations tell me that an average male produces around 8,157,500,000,000 individual sperm in his lifetime, give or take. Yet how many of those potential human beings actually go on to become human beings? One? Two? Three, maybe? None?

I once heard of a thought experiment that explains why assuming that other life exists in the universe, based on just a single data point, ourselves, is flawed. It goes along the lines of: imagine there are a million prisoners, each in their own cell, and none of them are aware of the other prisoners. They are all given a hairpin and told that if they can unpick the locks on the doors of their cells in under three minutes, they will be freed. If they fail to do this, they will die. What they don’t know is that the locks are impossible to pick, and they all die except one. He somehow manages to unpick his lock and free himself. When asked, after he was freed, how easy it was to unpick the lock, he replies that it was very easy. It must have been, as he managed to do it in under three minutes. He is then told of the other 999,999 prisoners who died, which naturally changes his whole view on just how easy it really was.

Are we that prisoner? Are we also making the mistake of assuming that just because we exist, it must be easy for life to come into existence? Whereas, in reality, the universe is littered with other prisoners who never made it? Of course, this neither strengthens nor weakens the argument for or against other life in the universe, but it does demonstrate quite well the pitfalls of confirmation bias, or assuming that just because we exist, others must also exist.

| Two possibilities. Only one proven outcome

As Arthur C. Clarke once put it, only two possibilities exist: either we are alone in the universe, or we are not. Both are equally terrifying. But the thing is, we will never know if we are alone in the universe. We can only ever know that we aren’t. For as long as we continue to exist without defining proof of other life, the possibility that it exists will always remain. You can’t prove a negative, as they say. We will only ever know the true answer to the question of whether we are alone or not when we encounter undeniable evidence that we are not, whatever form that takes. Until then, both possibilities will always remain.

And then, of course, we come to the famous Fermi Paradox, which asks the simplest and most fundamental question of them all: where is everyone? Although, as a side note, I’m not entirely sure why this question became so wedded to Enrico Fermi himself. He surely wasn’t the first to ponder such an obvious contradiction.

The universe has been around, as far as we can tell, for around 13.8 billion years. That’s a very long time for galaxies, solar systems, planets, and ultimately, life to form all across the universe. Earth has only been around for less than a third of that time, and yet, here we are. So, where is everyone else? We have been surveying the skies, arguably, since Galileo Galilei first invented the telescope, back in the early 17th century. Yet, despite our much more modern technology these days, we have yet to find evidence of any form of life whatsoever out there in the cold, dark vastness of space. We do, however, seem to find “Earth-like” planets with seeming regularity. This, again, is often put forward as yet more evidence that we can’t be alone in the universe. But you could also look at it the other way and say that the more “Earth-like” planets we find, whilst remaining unable to find any proof of extraterrestrial life, only goes to further demonstrate that simply being “Earth-like” and orbiting a star at just the right distance for water to exist in liquid form may not be anywhere near close enough to meet the seemingly very strict criteria needed for life to spontaneously form.

When people state that there simply must be other life in the universe, they are not speaking from a position of scientific theory; they are speaking solely from a position of faith. A faith that something must be true without any evidence or proof to back up the claim. There exist dozens of explanations and reasons for the Fermi Paradox, some plausible, many of them not so much. Our intuition in every other aspect of our existence tells us that if we have no evidence that something exists, the simplest explanation is that it simply doesn’t exist. It’s why very few of us believe in ghosts, fairies at the bottom of the garden, or, these days, even a deity.

| Conclusion

Do I really, honestly, believe that, out of the incomprehensible number of planets in our universe, we really are the only life? My honest and only logical answer to that is, I don’t know. But for as long as there remains no evidence to the contrary, we must always keep an open mind to the idea that, perhaps, we are. No matter what our intuition tells us. It wouldn’t be the first time our natural intuitions have been proven to be incorrect. The more we learn about ourselves and the nature of the universe we live in, the more we discover that hardly anything we experience is quite what our instincts and intuitions tell us it is. No one can surely deny that nature can be a Machiavellian beast.

But just imagine how special we would be if we were, in fact, the only consciousness in the entire universe. It is often suggested that we exist not in the universe, but as a part of the universe itself, and that, perhaps, we exist as a way for the universe to experience itself. I have some sympathy for this theory. Again, our intuition tells us that we look out at the universe as if it exists as a separate entity from ourselves, yet surely, we are not looking out at anything. We are, in many ways, looking at an extension of ourselves, not separated from us, but within us, as much as we are within it. It is often asked what the meaning of it all is. But if we really are the only way that the universe can truly experience itself, are we, ourselves, not the meaning? For as long as we exist, we, ourselves, give the universe meaning, purpose, and, above all, consciousness. If we really were the only consciousness to exist, what would happen if we were to somehow cease to exist?

With this in mind, the question has to be asked: without meaning, purpose, or any way to experience itself, would the universe not technically also be dead?

Until we find irrefutable proof that we are not alone in the universe, the possibility that we are will always remain, and if we are alone, we would be so special, we could very well be the only entities keeping the universe itself alive.